If you knew my dad for five minutes, he made you laugh. If you knew him for 50 years, he made you laugh more—usually at the least likely moment, which somehow made it better.

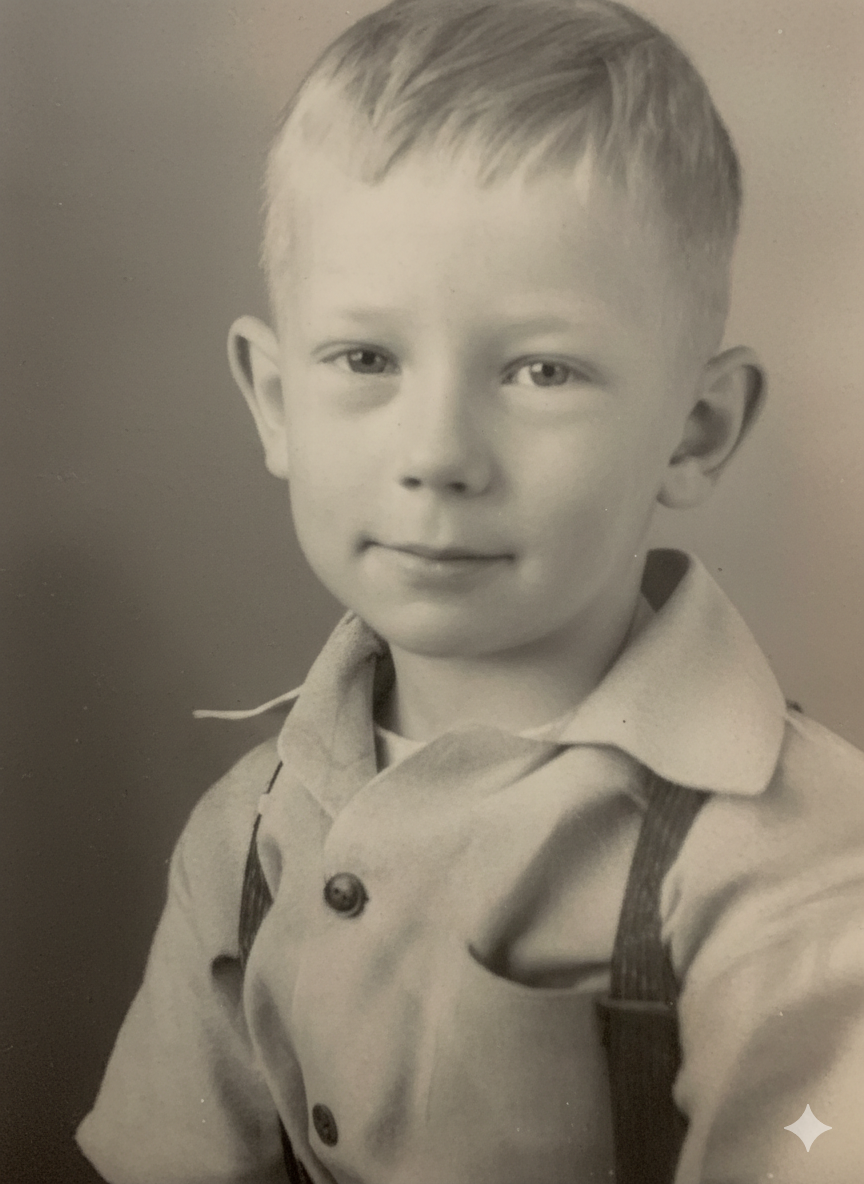

That was Jerome George Onkels. ‘Jerry’ to everyone who knew him—because, as he’d tell you, his parents clearly had it out for him. Jerome. George. He considered it a punishment.

So Jerry it was.

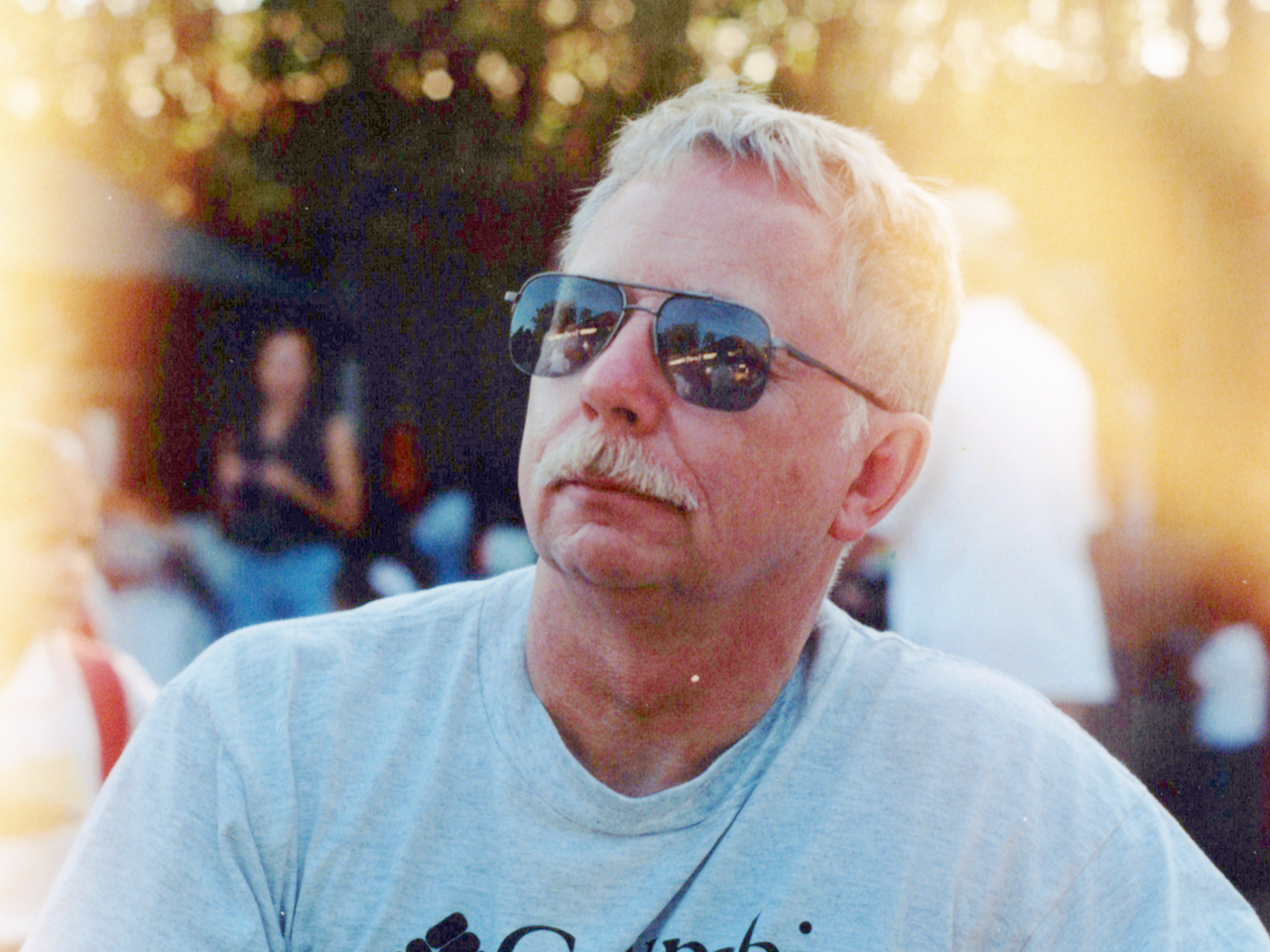

87 years old. Married to the love of his life for 61 of them. And hilarious until the very end.

Today, I’d like to tell you a little bit about my dad.

Not the version you put on a memorial card—the authentic version.

About the guy who worked as a urology technician for decades at the Mayo Clinic, which meant he spent most of his career in hospital rooms with nervous men in vulnerable situations. And somehow, every single time, he made them laugh. He put them at ease.

That was his gift. He could walk into the most awkward moment of your week and make you feel like everything was going to be fine.

He had this dry wit—never mean, never showy. Just perfectly timed. He once told me that when he was a kid, he wanted to be Superman. Then he said, “I gave up on that a couple weeks ago.”

He was 76 at the time.

Dad grew up in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, in a family that watched their pennies. Summer meant playing outside with the neighborhood kids—one football shared between all of them and coming home to fresh cookies and a glass of milk.

He didn’t have much, but he never talked about it like he was missing anything. That’s just how he was. He found joy in simple things and never lost that.

He served 3 years in the Army National Guard, earned his marksman qualifications, and eventually found his way out to Oakland, California.

That’s where he met Mom.

He was just giving his sister Barb a ride to a Catholic singles club—the Angeles Club. One night, a cute woman named Sandy asked if Dad could give her a ride home instead. They stopped for pizza. Talked for hours.

That was it.

They got married in November of 1964 at Our Lady of Lourdes Chapel in Oakland. And their honeymoon? It was…a complete disaster.

They drove their Volkswagen Beetle to Las Vegas through the worst snowstorm in fifteen years. Followed a semi-truck through zero visibility because Dad figured if the truck can make it, so will he. All the motels were full, so they ended up at a place called Popsicles—a truck stop with only cold-water showers. The next night, they found a restaurant advertising lobster for $2.

Dad said it tasted like broken glass.

And they were married for 61 years. Because Dad understood something important: circumstances don’t make a marriage. People do.

After the wedding, and after surviving that honeymoon, they moved back to the midwest, to Rochester, Minnesota, where they’d spend the next 50 plus years building their life together. The “bustling metropolis” of Rochester was home. That’s where they raised Mike and me, where they put down roots, where the grandkids came to visit. It’s where Dad meticulously raised miniature roses, carefully managing them through the harsh Minnesota winters.

A few years ago they moved to the Salt Lake area to be closer to Mike and lived in a shared room within an assisted living home, together, until the end.

Dad survived a lot.

Oakland in the sixties was no joke—he saw the riots, the Black Panthers, cops in bulletproof vests. He got mugged once in West Oakland. A man pretending to be drunk asked him for directions, then sucker-punched him. He went through his pockets and kicked him while he was down. Dad told me his only thought was, “As long as I get out of here alive, I’m okay.”

He got out. He always did.

Doctors and nurses were surprised by his resilience more times than I can remember. He came close to the edge and kept coming back. Not because he was lucky—because the man was stubborn, and resilient, fearless, and had people to stick around for.

In his later years, Dad volunteered at a local hospice for half a decade.

I asked him once—what do you say to someone who’s dying?

And he told me: “I don’t know what to say. I just ask them questions about their life and let them talk. It meant a lot to them.”

That was my dad. He didn’t try to fix anyone. He just showed up.

One of the hospice residents was a man named Sam. A former cowboy in his seventies, dying of cancer. Sam had kids, but they didn’t visit.

Sam loved Louis L’Amour novels. The cowboy books. So Dad read to him. He’d go in, read a chapter, try to leave—and Sam would say, “Read just a little more please.”

Pretty soon, Dad was spending 3, sometimes 4 hours a day reading old westerns to a dying cowboy.

He also learned that both he and Sam shared a love for fried walleye. Hospice food wasn’t cutting it. So Dad swung by Applebee’s, picked up an order, and brought it to Sam. They’d sit together. Sam would eat his walleye. Dad would read another chapter.

One morning, the nurses found Sam out of bed, packing a suitcase.

When asked what he was doing, he replied, “I’m packing.”

They followed it up with “Where are you going?”

Sam said: “Heaven.”

Sam died that evening.

I think about that story a lot. I know that Dad—just by being there, reading those westerns, bringing that walleye, asking about his life—gave Sam the company he needed to be ready.

That’s who my father was.

He wasn’t trying to save anyone. He wasn’t trying to prove anything. He just showed up. For Mom. For Mike and Evelyn, for me and Julie. For Natalie, Victoria, Alex, Amelia, Janessa, Joey, and Gio. For his sisters, Barb and Judy. His parents, friends and colleagues. For cowboys and men in exam rooms having the worst day of their week.

“Relationships are everything and family is everything. For all the material things in life, there’s nothing that comes close to it.”

That’s the man we’re here to remember.

That’s what he left us.

Thank you, Dad. We love you.